The History of Soap

Table of Contents

Soap-making in Antiquity

Mesopotamia

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Phoenicia

Ancient Greece

Roman Empire

Ancient China

The Medieval Soap Maker

Soap & The Renaissance

18th Century Soap

19th Century Soap

20th Century Soap

Modern Soap Making

THE HISTORY OF SOAP

Ever wondered about the history of soap or from where soap came? Combined, artisans and commercial manufacturers produce millions of bars of soap each year. Soap is something we easily take for granted in our modern times. Luscious moisturizing lather and aromatics are relatively recent additions in the timeline of soap. But to understand where soap started we have to know what exactly soap is.

What is Soap?

Three ingredients are required to make handmade soaps from scratch: Water, Lye, and Oil (animal or plant oil, not petroleum-based oil) These three ingredients, mixed in correct proportions, combine and chemically change into soap – a process called “saponification.“

In the history of soap making, there was a time when soap was harsh because the methods of making the soap were inaccurate as technology did not allow for the fine-tuning of lye in the soap. Lye heavy soaps were the result of an incomplete saponification reaction. The soaps worked fine for cleansing, but beyond that, there were no further benefits. (Read how soap works to remove dirt) Such were the sad early days in the history of soap making.

Who Invented Soap?

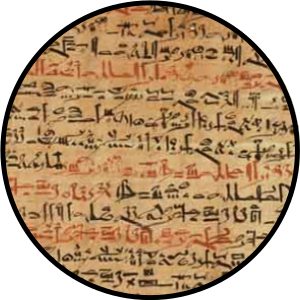

During the reign of Sargon of Akkad, Sumeria flourished in the arts and sciences. Because the knowledge of their soap making remains preserved in cuneiform writings on clay cylinders, we know they had knowledge of making soap. Miraculously the clay artifacts survived nearly 5,000 years giving us insight on our ancient ancestors and how they made soap. It is here that the invention of soap is believed to have occurred or rather our understanding of mixing alkali ash with oil produced a cleansing substance came to be.

In the mid-19th-century archaeologist unearthed these clay tablets dating to 24th and 23rd centuries BC. Cuneiform inscriptions on these tablets indicate that Cassia oil (same family as cinnamon) is boiled in water with ashes to create a paste for cleaning raw textile fibers. This discovery is believed to be the first reference to soap in the history of soap making.

The history of soap making has since evolved considerably over the millennia. Consequently, today anyone can learn and make beautiful & moisturizing artisan soaps far superior to those of our ancestors. Continue reading below to discover how soap has been made around the world from antiquity through modern times.

Use the nav dots on the right edge of the page to jump between sections. Use the table of contents on the above left to jump to specific countries and time periods.

History of Soap Making in Antiquity

Mesopotamia – Foundation of Soap, c. 2300 BC

In the mid-19th-century archaeologist unearthed clay tablets dating to the reign of Sargon of Akkad, king of Mesopotamia in the 24th and 23rd centuries BC. Cuneiform inscriptions on these tablets indicate that Cassia oil (same family as cinnamon) is boiled in water with ashes to create a paste for cleaning raw textile fibers. This discovery is believed to be the first reference to soap in the history of soap making.

Sargon of Akkad rules a vast empire. Ancient Mesopotamia is flourishing in the arts and sciences. It is here that the invention of soap is believed to have occurred or rather our understanding of mixing alkali ash with oil produced a cleansing substance came to be. Clay tablets recovered from archaeological digs contain the words fat and ash in a cuneiform inscription.

However, as these tablets are substantially damaged, the use or intention of the fat and ashes is unknown. Although considering the advanced level of the Babylonian civilization, it is likely that they are who invented soap and used it for textile cleaning and possibly for rituals. Unknown is whether the Babylonians used soap for personal cleansing. Perhaps one day another tablet will be found revealing more about old Babylonian soap.

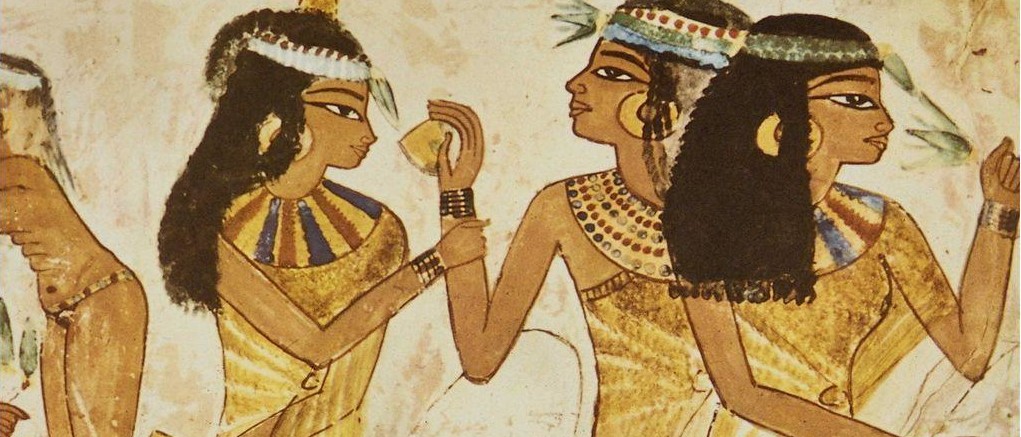

Ancient Soap Making in Egypt, 1550 BCE

The history of soap making in Egyptian antiquity remained hidden until the discovery of the Ebbers Papyrus. Possibly stolen from between the legs of a mummy in the Theban necropolis in the mid-1800s, the Ebers papyrus is amongst the oldest and most valuable medical papyri of ancient Egypt. Most noteworthy, it is an exquisite artifact. At 20-meters long, the 108 page scroll bears the date of the 9th year of the reign of Amenhotep I, 1550 BCE. (Greek- Amenophis I Ἀμένωφις).

The history of soap making in Egyptian antiquity remained hidden until the discovery of the Ebbers Papyrus. Possibly stolen from between the legs of a mummy in the Theban necropolis in the mid-1800s, the Ebers papyrus is amongst the oldest and most valuable medical papyri of ancient Egypt. Most noteworthy, it is an exquisite artifact. At 20-meters long, the 108 page scroll bears the date of the 9th year of the reign of Amenhotep I, 1550 BCE. (Greek- Amenophis I Ἀμένωφις).

The papyrus is colorfully written in hieratic Egyptian (the cursive form of hieroglyphics). The Ebers papyrus preserves for all time the most voluminous record of ancient Egyptian medicine and herbal knowledge. Scholars believe that the information on the papyrus was copied from earlier papyri dating as far back to Imhotep’s reign (c. 2650–2600 BCE)

Translations of the papyri’s hieroglyphics show that ancient Egyptians bathed regularly for not just personal hygiene but also medicinal and ceremonial purposes. Ancient Egyptians believed that an unclean body with unpleasant odors was impure and thus undesirable. The soaps they used however bear no resemblance to the soaps we use today. Most of these ancient soaps were a paste of ash or clay, mixed with oil, and sometimes scented. This resulted in a wonderful material that they used frequently to cleanse the body.

These translations are possible due to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799. Furthermore, alkaline salts such as Natron are noted to have medicinal uses for the skin. While these salts are sometimes used to make soap, it is not recorded in the Ebers papyrus whether ancient Egyptians had created or used soaps made from these salts.

Georg Moritz Ebers purchased the papyrus in the winter of 1873. This magnificent artifact currently resides in the library of the University of Leipzig, Germany.

Phoenicia, History of Luxury Soap Making Goods

Phoenicia, an ancient civilization that thrived along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Today this area is now Syria, Lebanon, and northern Israel. They had an esteemed reputation in shipbuilding and manufacturing of luxury goods. Pliny the Elder would speak of them when he wrote his book Naturalis Historia hundreds of years after the Phoenician empire fell. Pliny notes that the Phoenicians used goat fat and wood ashes for cleaning animal fibers for textile manufacturing.

Ancient Grecians – Oil, Ashes, and Strigils – Oh My

The ancient Grecians bathed primarily for aesthetic and socialization. They did not use saponified soap products. They preferred to clean their bodies with a mixture of clay, sand, pumice, and ash. They would coat their bodies and scrape off the mixture after anointing themselves with oil. They used a bronze instrument called a strigil to accomplish this.

The Roman Empire and the Barrels of Urine

Yes, you read that right. The Romans kept barrels on the street to collect urine. Since the urine would be left in the elements to decompose for a few weeks, it would break down into alkali components and then be used to wash wool. Aside from the gross factor, it was an ingenious way to recycle human waste and clean the animal wool. Ammonium carbonate [(NH4)2CO3] in the urine breaks down quickly into ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH)which is then used to saponify the oils and grease in the fibers.

In conclusion, the Romans bathing habits were similar to the Greeks in that they used a strigil also. Use of the strigil was their primary and preferred way to cleanse themselves of dirt and oil. Like the Greeks, bathing was a typically for socializing.

Mount Sapo Urban Legend

The fanciful story about Mount Sapo claims that upon its slopes, the ancient Romans sacrificed animals as burnt offerings to their gods. Wood ashes collected from the embers of their sacrificial altars mixed with the fats from the drippings, forming a simple type of soap. Rains would wash this soap into the nearby streams where the local women found that the soapy waters would cleanse their clothes better. The legend also implies that soap gets its Latin name, sapo, from the name of the mountain.

The fanciful story about Mount Sapo claims that upon its slopes, the ancient Romans sacrificed animals as burnt offerings to their gods. Wood ashes collected from the embers of their sacrificial altars mixed with the fats from the drippings, forming a simple type of soap. Rains would wash this soap into the nearby streams where the local women found that the soapy waters would cleanse their clothes better. The legend also implies that soap gets its Latin name, sapo, from the name of the mountain.

Let us deconstruct this legend and see the many reasons why the story is an improbable tale in the history of soap making:

Among the current geographical Italian names, no such name of Mount Sapo exist. Nor does the name appear in antiquity. The Latin word sapo was borrowed from early Germanic language and is cognate with the Latin ‘sebum’ which means tallow.

Animal sacrifices only included the bones and parts of the animal that could are edible. There would have been little to no fat to saponify in the ash. Citizens consumed the edible meat and fat from the sacrifice saving the remaining parts for their sacrifice to their gods.

History of Soap Making in Ancient China, c. 700 BC – 220 AD

Manufactured from the seeds of the Gleditsia Sinensis, the ancient Chineses created a detergent similar to soap. During the Zhou Dynasty, a traditional detergent made from pig pancreas and plant ash was used instead of saponified soap products. This combination of ingredients is known as “Zhu Yi Zhi” and is still produce today in rural regions of modern China. True soap, made of animal fat or plant oils, did not find its way in everyday households until our modern era. Ointments and creams are more popular than soap-like detergents.

Manufactured from the seeds of the Gleditsia Sinensis, the ancient Chineses created a detergent similar to soap. During the Zhou Dynasty, a traditional detergent made from pig pancreas and plant ash was used instead of saponified soap products. This combination of ingredients is known as “Zhu Yi Zhi” and is still produce today in rural regions of modern China. True soap, made of animal fat or plant oils, did not find its way in everyday households until our modern era. Ointments and creams are more popular than soap-like detergents.

Zhou Dynasty (c. 700–221 B.C.)

Nearly 3000 years ago during the Zhou Dynasty, the ancient Chinese discovered how to use specific plant ashes to remove grease. The sacred document “The Rites of Zhou” details the method they used. Interestingly, this information is in a script that covers the religious ceremonies of this Chinese dynasty.

Another document called the “The Record of Trades,” toward the end of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 700–221 B.C.), records how the Zhou methods of cleaning were greatly improved. Plant ash was mixed with crushed seashells, producing an alkaline based chemical that could remove the stains of light-colored silk fabrics

Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220)

During the Han Dynasty (206 BC) the Chinese discovered that ashes of the knotweed and wormwood contained a natural form of saponin. This natural alkaline substance could be extracted to make a type of soap.

During the Jin Dynasty nearly a thousand years later, saponin was formed into small ingots that sold at markets. Shops in Beijing were known for specializing in fragrant ingots shaped like fruit. Sadly these shops were shut down under the communist regime in the early 1950’s marking a sad period in the history of soap making.

History of Soap Making in Medieval Times

Despite common misconceptions, people living in medieval times had bathtubs and soap. Soap-making devices dating from the 700s have been excavated in Arabia, and the European Mappae Clavicula—written in the early 800s—includes soap-making directions. With care and some experimentation, modern crafters can recreate the soaps used in medieval times.

The Rise of Soap Making In Medieval England

Soapmaking by the English began during the 12th century. Wealthy women of the Tudor period imported and used ‘castile soap‘ for their daily washing. This expensive soap made from olive oil and was scented. During this period, instruction manuals indicate recipes for soap that suggest people from all classes of society were interested in personal hygiene. In the year 1633, King Charles I granted a 14-year monopoly to the artisans of the Society of Soapmakers of Westminister.

Bathing became quite popular during the reign of Elizabeth I. During this time, the use of soap was more considerable in England than any other European country. Sadly just as the soap industry was gaining momentum, heavy taxes were levied on soaps. These taxes remained until repeal in 1853, and soap making in England could flourish.

Medieval France Soap Making

Y

Medieval Italy

By the 7th Century, Italian soap makers organized into artisan craft guilds. Charlemagne’s Capitulare de Villis of 805 AD mentions the profession of a soap maker. By the 8th Century, soft soap made with oils was common in France, Italy, and Spain, as olive oil was widely available. Genoa, Venice, and Bari in Italy and Castile in Spain also became epicenters of soap making due to their natural resources. These countries had abundant supplies of olive oil. Barilla, a sodium-rich plant whose ashes were used to make soda lye, combined ideally to create a beautiful hard white bar of soap.

The History of Soap in the Age of Enlightenment

Renaissance, 14th – 17th Century

In France, by the second half of the 15th century, the semi-industrialized professional manufacture of soap was concentrated in a few centers of Provence—Toulon, Hyères, and Marseille—which supplied the rest of France. In Marseilles, by 1525, production was concentrated in at least two factories, and soap production at Marseille tended to eclipse the other Provençal centers. English manufacture tended to concentrate in London.

Finer soaps were later produced in Europe from the 16th century, using vegetable oils (such as olive oil) as opposed to animal fats. Many of these soaps are still produced, both industrially and by small-scale artisans. Castile soap is a popular example of the vegetable-only soaps derived from the oldest “white soap” of Italy.

Industrially manufactured bar soaps became available in the late 18th century, as advertising campaigns in Europe and America promoted popular awareness of the relationship between cleanliness and health. In modern times, the use of soap has become commonplace in industrialized nations due to a better understanding of the role of hygiene in reducing the population size of pathogenic microorganisms.

History of Soap in the Industrial Revolution

17th & 18th Century

In 1789, Cornish barber Andrew Pears opened premises in Soho, London (then a fashionable residential area), for the manufacture and sale of rouges, powders, and other preparations used by the rich to cover up the damage caused by the harsh soaps of the time. Pears was one of the first to recognise the potential of a purer, gentler soap that would be kinder to their fashionable but delicate alabaster complexions.

The upper classes associated tanned faces with the lower orders who worked outdoors. The manufacturing process he perfected, using purer ingredients, paying closer attention to each stage in the process, and adding a delicate perfume of flowers, remains substantially unchanged to this day.

History of Soap in Colonial America

Soap is considered one of life’s simple necessities. Unlike present-day soap makers, the colonials had to make their soaping ingredients. For months they would collect ashes leftover from burning hardwood. They would place them in what is called an ash hopper. This device was used to separate the lye from the wood ash. Water was poured over the ashes to leach out the lye. The solution was boiled until it reached a desirable strength.

Next, the soapmaker prepared the oils. Leftover cooking fat and uncooked animal fats were collected and rendered. This process boiled the fats in water until they were melted. Next, the fat was left to cool. As the mixture of fats cooled, impurities would settle on the bottom, and the rendered fat would solidify on top of the water. Colonial soap makers would perform this task outside as the smell of rendering fat is horrendous.

Once the necessary ingredients were ready, the soap maker could begin producing the soap. The lye solution is placed in a large cauldron with the rendered fat. The mixture of lye and fats was boiled for hours until it became bubbly and thick.

The success of colonial soap making was dependent on obtaining the correct balance between the lye and the fats.

The process did not involve precise measuring, and it sometimes required several attempts before a suitable batch was made. I’m guessing the references you read about ‘Grandma’s soap leaving your skin red and raw’ are a result of the process being so hit and miss!

Today, the art of making homemade soap is usually done for pleasure and the desire to make more natural, healthy choices. Though commercial soap is affordable and readily available, many people are finding it undesirable.

We are now aware that we are living in a world laden with chemicals and environmentally unsound products. As the website Natural Living For Women shows us, we can make natural choices that are beneficial to ourselves as well as the environment. Learning how to make soap is one of them.

There are a few different methods of making soap and each produces a product with its own unique qualities. Cold process soap making, the method mainly used on this site, hot process soap making, glycerin soap making, and liquid soap making are some of the most common.

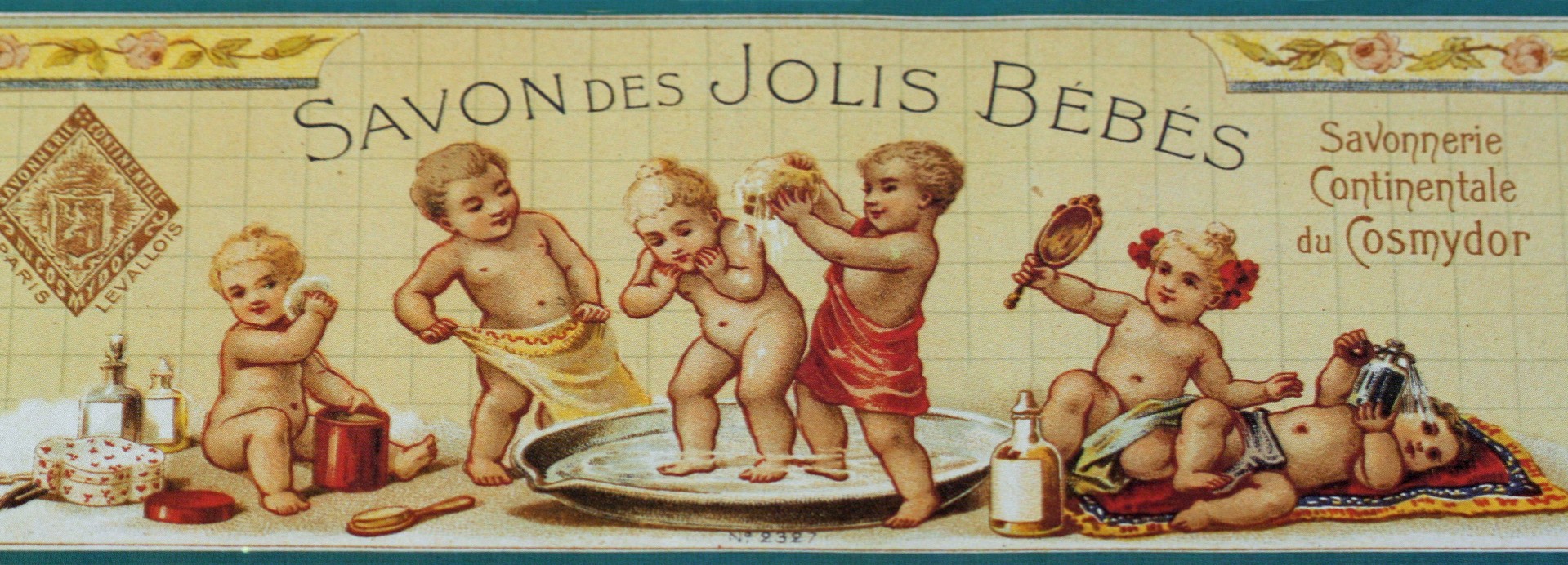

19th Century Soap Making

Sunlight Soap In the 1880s, William Lever leased chemical works in Warrington, where he experimented with different ingredients to manufacture soap. He settled on a formula of palm kernel oil, cottonseed oil, resin and tallow, and named it Sunlight soap.

It was an immediate success, forcing the company to move to a new and much larger factory by the river Mersey in Cheshire. People were now buying a particular make of soap rather than a type.

Like some other Victorian industrialists, Lever was a philanthropist. He built a model town to house his workers, calling it Port Sunlight after the soap it produced. Port Sunlight went on to develop other products like Lifebuoy carbolic soap, Sunlight soap flakes and Vim, each of which became a household name.

Ivory In 1840 the J.B. Williams Company in Glastonbury, Connecicut, manufactured soap under the name Ivorine. Williams decided to focus on its shaving soap and sold Ivorine to Procter & Gamble, who later renamed it Ivory.

In 1874 Procter & Gamble trademarked “Ivory”, the name of its new soap product. The name was created by Harley Procter, the founder’s son, who was inspired by Psalms 45:8 in the Bible: “All thy garments smell of myrrh, and aloes, and cassia, out of the ivory palaces whereby they have made thee glad.

As Ivory is one of P&G’s older products (first sold in 1879), P&G is sometimes called “Ivory Towers” and its factory and research center in St. Bernard, Ohio, is named “Ivorydale”.

Ivory’s first slogan, “It Floats!”, was introduced in 1891. The product’s other well-known slogan, “99 44⁄100% Pure” (in use by 1895), was based on the results of an analysis by an independent laboratory that Harley Procter hired to demonstrate that Ivory was purer than the castile soap

Ivory Soap, 1800s

Ivory bar soap is whipped with air in its production and in water. According to an apocryphal story, later discounted by the company, a worker accidentally left the mixing machine on too long and the company chose to sell the “ruined” batch, because the added air did not change the basic ingredients of the soap. When appreciative letters about the new, floating soap inundated the company, P&G ordered the extended mix time as a standard procedure. However, company records indicate that the design of Ivory did not come about by accident. In 2004, over 100 years later, the P&G company archivist Ed Rider found documentation that revealed that chemist James N. Gamble, son of the other founder, had discovered how to make the soap float and noted the result in his writings.

1900s

In October 1992, Procter & Gamble market-tested a new Ivory formula, a “skin care bar” that would address customer complaints about dryness but would not float like the original. In October 2001, P&G tested the sinking bar soap as part of an advertising campaign in the United States, in a six-month plan to release 1,051 soap bars that sink, among other bars that float, to see if people would notice the sinking bars, even if given a cash reward of up to $250,000The D. L. Blair company, part of Draft Worldwide, a unit of the Interpublic Group of Companies, was assigned to administer the contest.

Liquid soap was not invented until the nineteenth century; in 1865, William Shepphard patented a liquid version of soap. In 1898, B.J. Johnson developed a soap derived from palm and olive oils; his company, the B.J. Johnson Soap Company, introduced “Palmolive” brand soap that same year This new brand of soap became popular rapidly, and to such a degree that B.J. Johnson Soap Company changed its name to Palmolive.

In the early 1900s, other companies began to develop their own liquid soaps. Such products as Pine-Sol and Tide appeared on the market, making the process of cleaning things other than skin, such as clothing, floors, and bathrooms, much easier.

Liquid soap also works better for more traditional or non-machine washing methods, such as using a washboard.

20th Century Soap Making

1900s

In October 1992, Procter & Gamble market-tested a new Ivory formula, a “skin care bar” that would address customer complaints about dryness but would not float like the original. In October 2001, P&G tested the sinking bar soap as part of an advertising campaign in the United States, in a six-month plan to release 1,051 soap bars that sink, among other bars that float, to see if people would notice the sinking bars, even if given a cash reward of up to $250,000The D. L. Blair company, part of Draft Worldwide, a unit of the Interpublic Group of Companies, was assigned to administer the contest.

Liquid soap was not invented until the nineteenth century; in 1865, William Shepphard patented a liquid version of soap. In 1898, B.J. Johnson developed a soap derived from palm and olive oils; his company, the B.J. Johnson Soap Company, introduced “Palmolive” brand soap that same year This new brand of soap became popular rapidly, and to such a degree that B.J. Johnson Soap Company changed its name to Palmolive.

In the early 1900s, other companies began to develop their own liquid soaps. Such products as Pine-Sol and Tide appeared on the market, making the process of cleaning things other than skin, such as clothing, floors, and bathrooms, much easier.

Liquid soap also works better for more traditional or non-machine washing methods, such as using a washboard.

Modern Soap Maker

Make These Wonderful Historic Soaps

Here is a sampling from our collection of Historical Soap Recipes. These recipes will teach you how to make the soaps as they were made then. For modern soap recipes please visit our Recipe Vault where we have hundreds of free recipes for you to use.

Books on Soap Making

The Complete Guide to Natural Soap Making:

Create 65 All-Natural Cold-Process, Hot-Process, Liquid, Melt-and-Pour, and Hand-Milled Soaps

Paperback, March 26, 2019, by Amanda-Gail-Aaron (Author)

The Natural Soap Making Book for Beginners:

Do-It-Yourself Soaps Using All-Natural Herbs, Spices, and Essential Oils

Kindle Edition by Kelly Cable (Author)

Simple & Natural Soapmaking:

Create 100% Pure and Beautiful Soaps, The Nerdy Wife’s Easy Recipes and Techniques

Paperback, August 2017, by Jan Berry (Author)

Pure Soapmaking:

How to Create Nourishing, Natural Skin Care Soaps,

Spiral Bound, January 2016, by Anne-Marie Faiola (Author)

Soap Making Business:

How to Start, Run & Grow a Million Dollar Success From Home!

Paperback, December 2016, by Suzanne Carpenter (Author)

The Everything Soapmaking:

Learn How to Make Soap at Home

Paperback, December 2012, by Alicia Grosso (Author)

DIY Natural Hot& Cold Process Soap Crafting:

Ultimate Guide to Making & Selling Colorful Natural Soaps – Recipes Included

Paperback, February 2019, by Molly Barrett (Author)

Affiliate Disclosure: I am grateful to be of service and bring you content free of charge. In order to do this, please note that when you click links and purchase items, in most (not all) cases I will receive a referral commission. Your support in purchasing through these links enables me to keep Par Par Academy of Soaps & Cosmetics free, and empower more people worldwide to make soap safely and easily. Thank you!